Financing American government

3 The mechanics of government borrowing

In some respects, government borrowing is very similar to that of households and firms who borrow to buy cars, homes, machinery, and equipment. That is, the government borrows money from lenders to pay for its activities, and it promises to pay them back the borrowed amount plus interest in the future.

- treasuries

- The collective name for the bills, bonds, and notes issued by the US Treasury on behalf of the federal government. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Education Glossary.

- treasury bill

- A security issued by the US Department of the Treasury with original maturity up to one year.

- treasury note

- A security issued by the US Department of the Treasury with original maturity of 1 to 10 years.

- treasury bond

- A security issued by the US Department of the Treasury with original maturity of more than 10 years.

Specifically, the United States Treasury borrows money by selling government debt securities called treasuries. The date on which the loans are to be repaid is called the maturity date. The length of time between the issue date and the maturity date—the initial time to maturity—can be as short as four weeks or as long as thirty years. Three types of treasuries comprise most of the US debt: those that mature within one year, called treasury bills, those maturing in two to ten years, called treasury notes, and those with even longer maturities, called treasury bonds.

- coupon payments

- The regular payments received by the buyer of a bond. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Education Glossary.

Treasury bills are extremely simple contracts: a lender pays money to the government at the time of issue and gets paid back a larger amount at the time of maturity; no payments are made in the interim. Notes and bonds are different: they promise a stream of semiannual payments throughout the term of the loan, called coupon payments, in addition to the repayment of the loan amount on the maturity date.

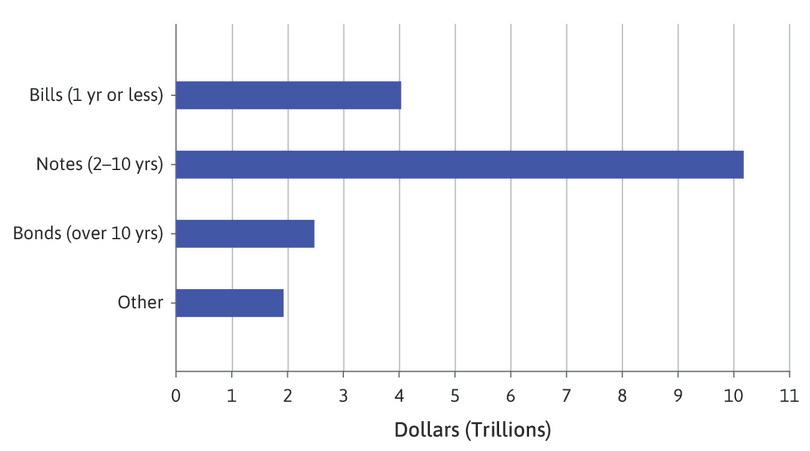

Figure 3 illustrates the maturity composition of US debt as of 30 April 2020. More than half of the government debt at this time was issued as notes, with about a quarter issued as bills. The figure shows the maturity composition at origination (that is, when the securities were first issued). Since many of the notes and bonds were issued years ago, some have maturity dates that lie within the next few months and will be due for repayment before some of the bills that are currently being issued.

Figure 3 Maturity composition of US government debt at origination (April 2020).

‘Monthly Statement of the Public Debt of the United States: 30 April 2020’, The Bureau of the Fiscal Service, retrieved from Treasury Direct, 25 November 2020.

- secondary markets and primary markets

- The primary market is where goods or financial assets are sold for the first time. For example, the initial sale of shares by a company to an investor (known as an initial public offering or IPO) is on the primary market. The subsequent trading of those shares on the stock exchange is on the secondary market. The terms are also used to describe the initial sale of tickets (primary market) and the secondary market in which they are traded.

- monetary policy

- Central bank (or government) actions aimed at influencing economic activity through changing interest rates or the prices of financial assets.

- open market operation

- The purchase and sale of securities in the open market by the Federal Reserve. A key tool used by the Federal Reserve in the implementation of monetary policy. Source: Federal Reserve Board.

Treasury auctions are the markets through which securities enter the economy, and they are called primary markets. Once these securities have been issued, they can be bought and sold on secondary markets. Essentially, the government has borrowed money in exchange for promises to pay, and these promises can be freely bought and sold.

The Federal Reserve is an important participant in the secondary market and has the legal authority to buy and sell treasuries without limit. Prior to 2008, the Fed would buy and sell treasuries in order to conduct monetary policy by maintaining its interest rate target, a process called open market operations. Since then, it has shifted to setting the interest rate paid on commercial bank reserves, a process we describe later in the Insight. In either case, Fed interest rate policy directly affects the behavior of bidders in the primary market for treasuries and can prevent interest rates from rising even when the borrowing needs of the government rise sharply.

Each year, the Treasury organizes more than 300 auctions that are open to the public. In a treasury auction, individuals and financial institutions bid for securities by specifying the minimum acceptable interest rate. These bids, together with the government’s borrowing needs, determine the market clearing interest rate, at which supply and demand are equated. Lenders who are willing to accept this rate are able to buy the securities, and all receive the same rate regardless of their individual bids. A detailed look at the workings of a treasury auction is provided in the Treasury auctions section.

Understanding how treasury auctions work helps us to see the hypothetical effects on the interest rate of an increase in borrowing needs (the actual effect will depend on the Fed’s response, as we shall see later in the Insight). In the example in the Treasury auctions section, if the borrowing needs were $70 billion, the market clearing rate would have been 0.14%. If the borrowing needs were $180 billion, all bidders would have been successful, and the market clearing rate would have been slightly higher at 0.16%. And if the government needed to borrow even more than this, the auction would have failed: the borrowing needs could not have been met.

- Federal Reserve Bank

- One of 12 regional Banks providing services to commercial banks, serving as fiscal agents for the US government, and conducting economic research on its region and the nation. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Education Glossary.

The failure of a treasury auction would precipitate a political and financial crisis, and is extremely unlikely to happen, in part because the Federal Reserve Bank has the power to buy as much government debt as it feels is necessary to maintain financial stability. In practice, the Fed does not need to involve itself in the market for treasuries directly: its monetary policy targets and announcements can provide enough incentives for private bidders to demand treasuries in vast quantities at rates only slightly higher than the Fed’s policy interest rate. This makes the debt very secure, with bidders quite certain that they will be repaid in full and on time. Consequently, the market for US Treasury debt involves participants from around the world.

Treasury auctions

A treasury auction begins with an offering announcement that specifies the auction date, issue date, and maturity date, as well as the amount of the security on offer. On 21 May 2020, for instance, the Treasury announced an auction for a 13-week bill, with issue date 28 May, maturity date 27 August, and an offering amount of $63 billion. This amount was based on the borrowing needs of the government at that time.

Bidders name their price, which in the case of treasuries is the interest rate they would be willing to accept to lend the government a specific amount of money. The auction was held on 26 May, and the total demand for bills was about three times the amount on offer. Bids came in as low as 0.09% at an annual rate, and the market clearing rate was 0.13%. A summary of this information is in Figure 4, where the market clearing rate is referred to as the ‘high rate’ and the lowest bid received as the ‘low rate’.

Treasury auction results Term and type of security 91-day bill CUSIP number 912796XG9 High rate 0.130% Allotted at high 80.97% Price 99.967139 Investment rate 0.132% Median rate 0.120% Low rate 0.090% Issue date 28 May 2020 Maturity date 27 August 2020 Figure 4 Results from a treasury bill auction.

Data from TreasuryDirect.

The manner in which these prices and rates are determined at an auction is as follows. Bidders submit the lowest interest rate that they are willing to accept, as well as the amount of the security that they want to buy. What they are buying is a promise of payment on the maturity date. The bids are sorted from lowest to highest, and those with the lowest bids get the requested securities until the government’s demand for borrowing has been met. The market clearing bid is the one that pushes the total demand for securities just above the available supply, and this is the interest rate that all bidders receive. The bidder (or bidders) who submit exactly the market clearing rate may not get the full loan amount requested.

To see exactly how this works, consider the following set of hypothetical bids that is roughly consistent with this data (all quantities are in billions of dollars):

Bidder Bid Rate (%) Quantity A 0.09 10 B 0.11 15 C 0.10 10 D 0.12 20 E 0.14 30 F 0.14 15 G 0.14 25 H 0.16 10 I 0.15 35 J 0.13 10 Total 180 Suppose that the offering amount is $63 billion so not all bidders will get securities. To see who does, and in what amounts, we sort the bidders based on their bid rates to get:

Bidder Bid Rate (%) Quantity Allocation A 0.09 10 10 C 0.10 10 10 B 0.11 15 15 D 0.12 20 20 J 0.13 10 8 E 0.14 30 0 F 0.14 15 0 G 0.14 25 0 I 0.15 35 0 H 0.16 10 0 Total 180 63 Now we see that bidders A, C, B, and D are the lowest four bidders and collectively want bills amounting to $55 billion, so they get their requested amounts in full. Bidder J is next, and gets the remaining $8 billion which is somewhat less than the requested amount. In the actual auction shown in Figure 4, those who bid exactly the market clearing rate received about 81% of their demand, as indicated on the line ‘Allotted at High’. The market clearing bid comes from this bidder, and is equal to 0.13%. Once this rate is determined, it is offered to all successful bidders, regardless of what they would have been willing to accept. Those bidding more than this rate get no bills; they are asking for an interest rate that is too high.

Treasury notes and bonds are a little more complicated: the promise being purchased is a stream of semiannual payments, and a larger payment on the maturity date. But the process of allocation is much the same: individuals bid for the securities, the market clearing bid is the interest rate at which demand and supply are equated, and those with this bid or lower get the securities.

Question 2 Choose the correct answer(s)

Use the information provided in the Treasury auction section to select all of the statements below that are correct.

- Bidder A and Bidder C both purchased $10 billion in securities at the market clearing rate of 0.13%. Their payments after 13 weeks will, therefore, be the same.

- Although Bidder B’s bid rate was 0.11%, the market clearing rate is 0.13%. Therefore, at the end of 13 weeks, Bidder B will get back $15 billion plus interest calculated at an annual rate of 0.13%.

- Bidder G’s bid rate of 0.14% was above the market clearing rate of 0.13%. Bidder G, therefore, will not get any treasuries in this auction.

- The bid rate is not what the bidder is willing to pay, it is rather the interest they will accept in exchange for loaning money to the treasury.

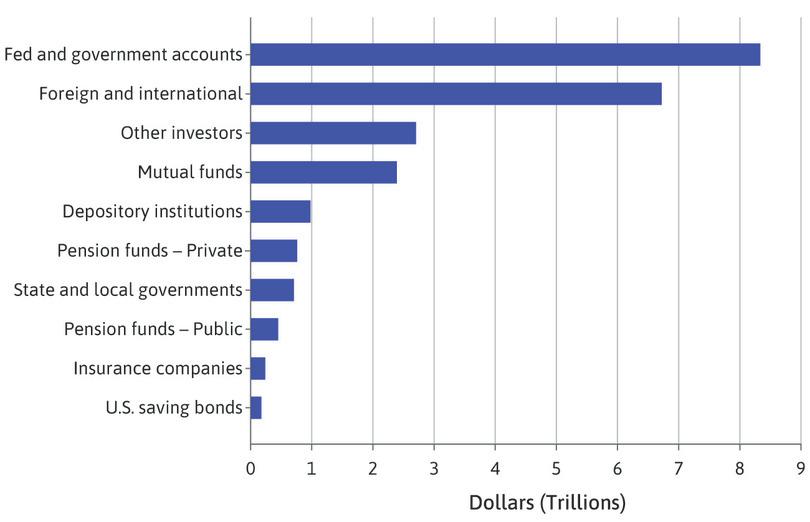

Figure 5 Estimated ownership of US Treasury securities (December 2019).

‘Estimated Ownership of US Treasury Securities [OFS-2]’, The Treasury Bulletin. June 2020. Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Services, retrieved from the Bureau of Fiscal Services, 25 November 2020.

Figure 5 shows the ownership distribution of treasuries in June 2020. Foreign investors hold approximately 29% of the US debt, with Japan and China having the most significant holdings. The Fed and other government accounts such as the Social Security Trust Fund hold about 36%. Much of the rest is owned by private investors in the US, either directly or indirectly through mutual funds and pension funds. Depository institutions such as banks, and state and local governments also have significant treasury holdings.

About 11% of the debt is held by the Federal Reserve. In fact, this figure underestimates the role of the Fed in the market for treasuries, for reasons that we consider next.