Financing American government

6 A new monetary policy mechanism

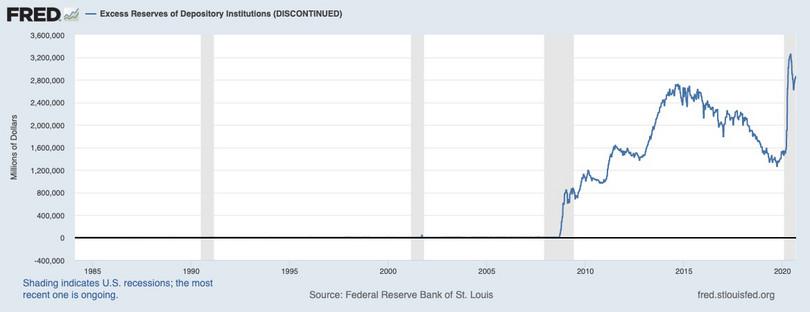

Prior to 2008, banks did not receive interest on deposits held at the Fed, so excess reserves were lent out through the fed funds market, or used to buy assets, including treasuries. But this situation changed dramatically during the crisis, as can be seen in Figure 8. The Fed began to pay banks for excess reserves held in their accounts, and the banks, in turn, chose to maintain substantial deposits at the Fed, instead of using the surplus to buy assets on the open market.

Figure 8 Excess reserves of depository institutions (weekly).

‘Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Excess reserves of depository institutions [EXCSRESNW]’, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 25 November 2020.

- interest rate on excess reserves (IOER)

- The interest paid on funds that are above the reserve requirement. IOER is determined by the Federal Reserve and it is used as an additional tool for the conduct of monetary policy.

With interest rates on excess reserves, the Fed had a new monetary policy tool that could be used to affect the fed funds rate, and through that the entire range of rates in the economy. If the fed funds rate fell below the interest rate on reserves, banks would deposit excess reserves in their Fed accounts instead of lending them in the interbank market, and the reduced supply would raise the fed funds rate. Similarly, if the fed funds rate rose above the interest rate on reserves, banks would withdraw excess reserves from their Fed accounts and lend them in the fed funds market. In this case, the increased supply of money in the fed funds market would bring the fed funds rate down. Through this effect, the two rates track each other very closely.

For similar reasons, interest rates in the market for treasuries would be anchored by the fed funds rate. If treasury bills were offering higher interest rates, banks could borrow in the fed funds market (or withdraw reserves from Fed accounts) to buy treasuries on the open market, or bid for them at auction. With the Fed targeting this key interest rate, the rate of treasury bills is pinned down, even when government borrowing needs rise. As a result, a surge in the deficit need not result in costlier borrowing for the government.

This is all true provided that the Fed does not begin to fear inflation. Were it to do so, it would raise its target for the fed funds rate, thus raising the cost of borrowing for households, firms, and the Treasury itself. Deficits can result in higher interest rates if they lead to increased fears of inflation. And this is unlikely in crisis conditions when unemployment is high and aggregate demand low.

Expansionary monetary policy works by lowering the interest rates banks charge on loans to households and businesses, which can stimulate borrowing and aggregate expenditure. This works well if rates can indeed be lowered, and demand for borrowing is responsive to the lower rates. In crisis conditions, neither of these conditions may hold: interest rates may already be close to zero, or lowering them may do little to stimulate borrowing. In this case, the Fed may engage in unconventional policies: buying treasuries with longer maturities, or other assets in the economy. We consider this next.

Question 5 Choose the correct answer(s)

Use Figure 8 and the information you have just read to select all of the correct statements below:

- Prior to the 2007–2008 global financial crisis, excess reserves never exceeded $40 billion in any week.

- In the week ending 27 May 2020 excess reserves were $3.252 trillion.

- It was not changes in the reserve requirement but rather a new policy of paying interest on excess reserves that contributed to the dramatic increase observable in Figure 8.

- A new policy of paying and adjusting interest on excess resulted in the increase in excess reserves.